We now continue with verse 11:

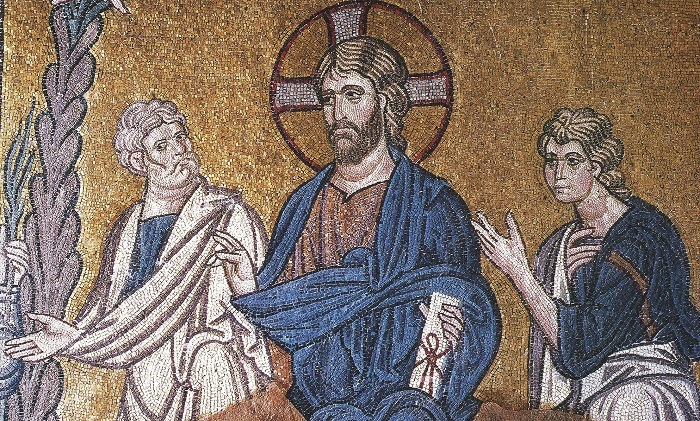

The reflections of St. John Cassian explain the deep meaning of the Lord Jesus Christ’s temptation and how this relates personally to each one of us:

“The Savior, having the incorrupt image and likeness of God, also had to be tempted in the same passions in which Adam was tempted while he was still in a state of innocence, namely: the passions of gluttony, vainglory, and pride. Gluttony—for which Adam ate the forbidden fruit from the tree; vainglory—when the devil said to the forefathers that their eyes would be opened; and pride—about which he said: you will be like gods, knowing good and evil (Genesis 3:5). Thus, the Lord and Savior was also tempted in these very passions. Gluttony—when the devil said: command that these stones become bread; vainglory—when he said: If you are the Son of God, cast Yourself down; pride—when showing the Lord all the kingdoms of the world and their glory, the devil said: All these things I will give You if You fall down and worship me (Matt. 4:3, 6, 8–9). The Savior allowed these temptations so that He might teach us, by His own example, how we must overcome the tempter—namely, by the very same means with which the Lord rejected him. Thus, Jesus Christ needed to endure these specific temptations; and more than this was unnecessary. For he who overcomes gluttony cannot be tempted by lust, which arises from satiety—the very root through which Adam himself would not have been tempted had he not, being deceived by the devil, first yielded to the passion that gives rise to lust. Therefore, it is not said of the Son of God that He came in sinful flesh, but in the likeness of sinful flesh (Rom. 8:3), because He had a true human body: He ate, drank, slept, and truly suffered torments on the cross—but the sinful inclination of the flesh, which gave rise to transgression, He did not possess. For Jesus did not feel the burning sting of carnal desire that wounds us against our will because of our fallen nature… Therefore, the devil tempts Jesus only in those passions through which he deceived the first Adam, supposing that Jesus, as a man, would likewise be deceived in other passions if he succeeded in tempting Him in that which had caused the downfall of the first man. However, once defeated in the first battle, the devil was no longer able to inflict upon Jesus a second wound—namely, to awaken the carnal desire that stems from the original sin of gluttony.”

Fr. Daniil Sysoev, who bore a martyr’s crown in our own time, warned against a misconception often heard among some believers, which is used to justify their lack of ascetic struggle and personal laziness. This idea is expressed in the saying: “It was easy for Christ—He was God!” But we know that Jesus is not only God—He is also man. More precisely, He is the God-man, and for this reason He endured all the hardships and sufferings of life on earth. The Lord was in no “privileged” position compared to us. On the contrary—as the Apostle Paul writes: For in that He Himself has suffered, being tempted, He is able to aid those who are tempted (Heb. 2:18).

Let us continue with verse 12:

Now when Jesus heard that John had been delivered up, He withdrew into Galilee.

Saint John Chrysostom thoroughly explains the reason for Christ’s departure from Judea to Galilee:

“Why does Jesus withdraw again? In order to teach us not to expose ourselves to temptations, but rather to avoid and withdraw from them. One is not to blame who does not cast himself into danger, but he who, once in danger, lacks courage. Therefore, to instruct us in this, and to temper the hatred of the Jews, Christ withdraws to Capernaum, fulfilling the prophecy. At the same time, like a fisherman, He might catch the future teachers of the universe (here the saint refers to the Apostles), who, occupied with their craft, lived in this city. Notice here how Christ, whenever He intends to depart to the Gentiles, always uses the hatred of the Jews as the occasion.” That is to say, Saint John points out that the Jews could not accuse Christ of refusing to preach to them and of preferring to go to the Gentiles, since it was precisely their hatred that drove Him toward the Gentiles.

Saint Cyril of Alexandria adds a very significant insight, saying:

“Christ withdraws from Judea toward the Gentiles, thus showing that He abandons the Jews not only when they offend God, but also when they sin against the holy Prophets.”

Regarding the imprisonment of John, Saint John Chrysostom notes that Herod was incited to this action, among other reasons, by the elders of the Jewish people, since the Forerunner also reproached them and did not spare them. It was therefore to be expected that they would also rise up against Christ. This was the reason for the Lord’s withdrawal from Judea to Galilee, teaching us that we should not place ourselves in danger without great necessity.

Galilee was a densely populated region. According to the Jewish historian Josephus Flavius, there were more than two hundred cities and settlements in the region, and it is estimated that around four million people lived there. Even the smallest settlements had around fifteen thousand inhabitants. Trade was highly developed, and many caravans passed through Galilee. The land was fertile, and nearly every piece of ground was cultivated and bore abundant fruit. The population was mixed, consisting of Jews and Gentiles—Greeks, Arabs, Egyptians, and others. Precisely because of this mixture, they were the object of disdain from the Jews of Judea. Yet it was also due to this intermingling that the Gentiles had the opportunity to hear from the Jews about the coming Messiah. A confirmation of this may be seen in the words of the Samaritan woman in her conversation with the Lord, as she says: “I know that the Messiah is coming, who is called Christ; when He comes, He will tell us all things” (John 4:25).

In Galilee, the Lord Jesus spent most of His time preaching; there He worked miracles, and there He chose His Apostles from among the simple Galilean fishermen. In Galilee, the ignorance of God was greater—this was another reason why the Jews looked with such contempt upon the Galileans. Therefore, the Pharisees and scribes said to Nicodemus, a secret disciple of Christ: “Are you also from Galilee? Search and look, for no prophet has arisen out of Galilee” (John 7:52). There were no educated scribes in Galilee, as there were in Jerusalem and Judea. However, the positive side of this situation was precisely that the Galileans were not as infected with various prejudices and false expectations concerning the coming Messiah, as was the case with the Jews. Naturally, the Galileans were not entirely free of prejudice, but the root of their misconception came from ignorance, while among the Jews it stemmed from pride and arrogance.

Now the following verses, Matthew 4:13–16, read:

And leaving Nazareth, He came and dwelt in Capernaum by the sea, in the regions of Zebulun and Naphtali, that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the prophet Isaiah, saying: “The land of Zebulun and the land of Naphtali, by the way of the sea, beyond the Jordan, Galilee of the Gentiles—the people who sat in darkness have seen a great light, and upon those who sat in the region and shadow of death light has dawned.”

The Lord settled in Capernaum, a city referred to in the Gospel of Matthew as “His own city”: And getting into a boat He crossed over and came to His own city (Matt. 9:1). Far from being a bastion of piety, Capernaum was among the cities that the Lord sharply rebuked, saying: And you, Capernaum, which art exalted unto heaven, shalt be brought down to hell; for if the mighty works, which have been done in thee, had been done in Sodom, it would have remained until this day (Matt. 11:23). Today, there is a tendency among some Christians to equate urban life with apostasy from the Lord, while rural life is seen as inherently ideal for Christian living. Yet throughout the history of the Church, many Christians have lived not only in cities but even in the major world capitals of their time—just as they do today. Whether or not one is saved does not depend so much on one’s location as on the exercise of free will. St. Ambrose of Optina gave sound advice for Christians living in cities: “One may live in the world, but not in its hustle—live quietly.” St. Ephraim the Syrian similarly notes: “It is not the place that saves a man, but his intention. Our forefather Adam fell in Paradise, while the righteous Lot preserved himself even in Sodom.”

St. John Chrysostom explains what is meant by darkness in this context: “By ‘darkness,’ the prophet does not refer to ordinary darkness, but to delusion and godlessness, which is why he adds: The people who sat in darkness have seen a great light; and upon those who sat in the region and shadow of death, light has dawned. To make it clear that this is not about physical darkness or light, the prophet does not simply refer to light, but to a great light, which elsewhere is called the true Light (John 1:9). As for the darkness, he describes it as the shadow of death.” The saint goes on to expound a great truth—that we are not saved by our own will or deeds, but solely by the will and grace of God: “To show that the inhabitants of this land did not seek or discover the light on their own, but that God revealed it to them from above, the Evangelist writes: the light has dawned—that is, the light itself shone and illumined them, rather than them having taken the initiative to draw near to it. In truth, the human race at the time of Christ’s coming was in a most pitiable state; people were not even walking in darkness—they were sitting in it. This means they had lost even the hope of deliverance from the darkness. They did not know where to go, and, overcome by the darkness, they sat, having no strength even to stand.”

Adapted for contemporary readers based on the patristic commentaries by: Stanoje Stanković